Prologue to An American Bum in China by Tom Carter

What became of Evans after illegally crossing into Burma

It was just about midnight when Matthew Evans burrowed rodent-like through a hole in a fence in southwestern China’s subtropical Yunnan Province and illegally crossed the border into Burma.

The jagged opening in the iron rails had already been cut out, probably years earlier, and was one of countless unlawful points of entry between Ruili, a bustling Chinese bordertown on the Shweli River, and the small Burmese city of Muse.

Despite the two-mile-long, ten-foot-high containment gate that surrounds Ruili, it is an open secret, quite literally, that the southern Yunnan border at Burma is rife with illegal immigration and human trafficking.

For centuries the lush Ruili region has served as a trading crossroads for Southeast Asian merchants and their Chinese counterparts, though in recent decades it has also become a kind of Wild Wild East outpost teeming with prostitution and drug traffickers moving weight up from the Golden Triangle.

Most migrants and merchants, however, are attempting to make their way into China’s economic wonderland to chase their pleasures and dig their treasures, not out, which was the direction Evans was taking.

A five-minute stroll away from Ruili’s ostentatious, gold-flecked port of entry, the twenty-seven-year-old American came across his first opening in the gate, straight, deep, and wide. Humming in his head the Doors’ “Break on through to the other side,” Evans broke into Burma.

Contrasting bleakly with Ruili’s neon spectrum of karaoke bars and brothels glowing behind him, Muse was forbiddingly dark and closed for the night. With no map and no semblance of the town’s layout, Evans asked a passerby for directions to the nearest bus station, which hopefully would take him a thousand kilometers to the former capital city of Rangoon.

There, according to a mysterious Burmese man he had spoken with a couple days earlier in Ruili’s wretched hive of scum and villainy, Evans was assured that he would be paid fifteen thousand U.S. dollars for his precious U.S. passport.

Dreamfully driven to do things regardless of their consequences, Evans was singularly determined to get this money — and willing to compromise China’s ter- ritorial integrity, sell out his own country’s national security, and brave Burma’s ongoing civil war in order to obtain it.

A mere fifteen minutes after Evans believed he had successfully snuck into Burma, two men on old-model motorcycles pulled up revving alongside the lone white boy walking down Muse’s unlit main street.

“We’re police, show us passport!” they demanded in broken English.

Evans had lived in China long enough by now to know when he was getting hustled; damned if he would just hand over his most valuable possession to a stranger.

“If you’re police, show me your badge,” Evans shouted back.

Without waiting for their response, he made his way toward a nearby hotel where he could hopefully take refuge. The lobby lights were off and the doors locked. Evans banged loudly on the glass, but the startled, sleepy security guard on the other side refused to open for the pale-faced apparition.

The men on motorcycles sped off. The next block down was another hotel, the only building in sight with an illuminated marquee, which he strode toward. As Evans approached the front doors, a car skidded to a halt in front of him. A dark-brown fellow leapt out and approached him.

After some tense back-and-forth asking Evans his na- tionality and purpose in Muse, the man, dressed in jeans, a T-shirt, and sandals, claimed he too was police and also asked to see Evans’ passport. It was tucked in his underwear; Evans told him that he had lost it after crossing the border and was on his way to the American embassy in Rangoon to get a replacement.

The maybe-policeman kept up his pretense, escorting Evans inside the hotel and instructing the front desk clerk in Burmese to give the foreigner a room, “but not let him leave,” he added in English for Evans’ benefit.

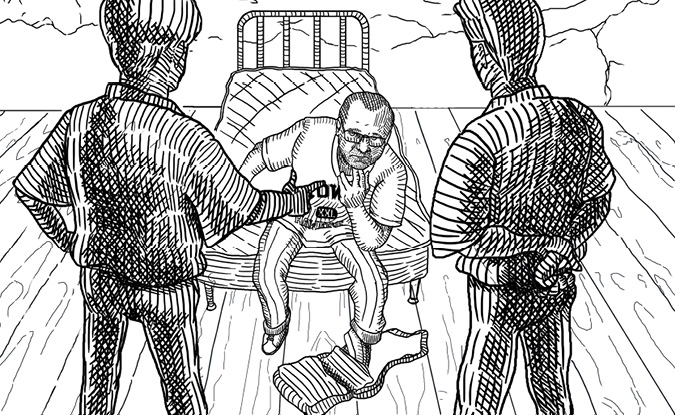

Less certain now that he was being conned, Evans did what he was told and checked into a room on the third floor of the Yun Yan Hotel. He had just relieved himself in the bathroom when the man returned, this time with an older comrade, besandaled and dressed casually, claiming to be the Chief of Muse Police.

“Ruili border does not issue visas and does not allow overland entry for foreigners,” the chief said matter-of-fact-ly in accented English while the other man rummaged through Evans’ satchel — searching, he said, for drugs but probably also for cash or his passport. “Our immigration office does not have any record of an American entering Muse.”

Evans, pretty darn sure now that these were real cops but still unsure if they were trying to shake him down, as third-world authorities are wont to do, placed his hands deferentially in his lap. He was trying to think of something clever to say, but couldn’t.

Evans, pretty darn sure now that these were real cops but still unsure if they were trying to shake him down, as third-world authorities are wont to do, placed his hands deferentially in his lap. He was trying to think of something clever to say, but couldn’t.

The south-Asian summer humidity got the worst of him and he began sweating heavily in his daffodil-yellow Iowa Hawkeyes tee. He dared not lift his hand to wipe the per- spiration fogging up his glasses.

“Normally what we do with illegals is just throw you in a jail for a few years. We have civil war right now. Nobody would ever know. I could be very cruel to you,” the chief continued with an intensity that kept Evans obedient. “But your president, Obama, is new best friend to Thein Sein. You know Thein Sein?”

Evans nodded his head even though he had no idea what a Thein Sein was. All he knew was that Burmese prison would be far worse than any Chinese jail, where Evans had already done time and where he was certain he was headed to again if the chief delivered him to Chinese immigration.

The chief and his underling escorted Evans outside to an unmarked car and placed him in the back seat. However, they didn’t go to the border station for an official handover. Instead, Evans was instructed to direct them to the exact same opening he had crawled through. It wasn’t hard; Evans had a knack for remembering topographical details, which got him his nickname, the Gopher, among his small circle of fellow expats back in Shanghai.

“You will go through that hole,” the chief said as the other man forcibly nudged Evans back into the People’s Republic of China. “And you will never return to Muse.”

He did what he was told and crawled through. In spite of the lifelong limp in his left leg, Evans scurried away as quickly as he could from the permeable border gate, but then suddenly stopped in the dark.

“Dang it!” he cursed aloud, realizing his fatal mistake. You see, while waiting in the Yun Yan Hotel for the police to return, the Iowan did something that, unforeseeable in the dense fog of his head, would thrust him into statelessness, homelessness, and the grand finale of his five epic years in China:

To keep the cops in Muse from getting their hands on his fifteen thousand dollar passport, Evans had tossed it out of the hotel’s bathroom window while peeing. Now he had to get back into Muse to retrieve it.

Buy the book